Charlemagne

Charlemagne was the first medieval emperor to rule from Western Europe. After the death of his father and brother, he became the sole ruler of the Franks. In the first decades of his reign, he concentrated on securing and expanding his empire.

In numerous campaigns he extended his empire’s borders ever further. He eventually ruled over a territory that, at the time of its greatest expansion, extended from Spain to Saxony and from Denmark to Central Italy. Motivated by his deep faith, he Christianised the pagan Saxons, not shying away from violence.

As the culmination of his political ambitions, he was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III in Rome at Christmas in the year 800.

Aachen as the capital of the empire

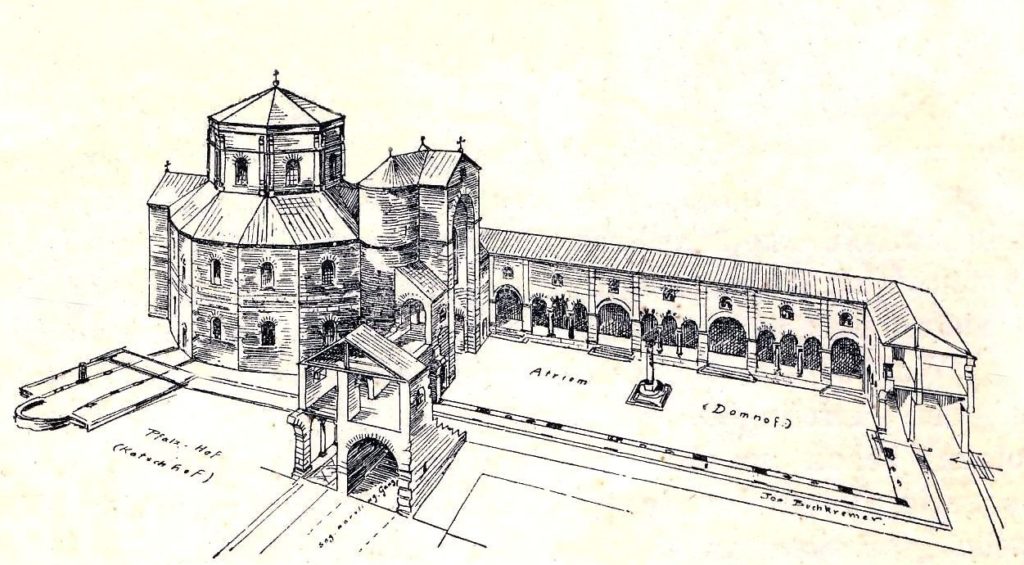

That Charlemagne would choose Aachen as his most important residence is anything but a given. A Roman settlement in the area of today’s city centre already existed shortly before the birth of Christ. There is also archaeological evidence that a Merovingian chapel and an imperial palace existed in Aachen during Pippin’s reign. Back then, Aachen was surrounded by forests with abundant game and was already renowned for its thermal springs, which Charlemagne himself highly esteemed. Apart from its geographic location at the centre of the empire, however, Aachen had no real significance.

Aachen’s importance increased when Charlemagne decided to expand his father’s existing estate and make it his main residence. For a short period of time, little Aachen became the political centre of the largest empire that had developed on European soil since the end of the Roman Empire.

Carolingian Renaissance

Under Charlemagne, the court became the intellectual centre of the empire. When in his later years the Frankish emperor settled down, he surrounded himself with the intellectual elite from all parts of his empire. Following the ideals of antiquity, but based on Christian traditions, many reforms in literature, language, education and architecture emanated from the court of Charlemagne. The military, judiciary and coinage were reorganised, bishopric and monastery schools were founded, and a new script – the Carolingian minuscule – was introduced.

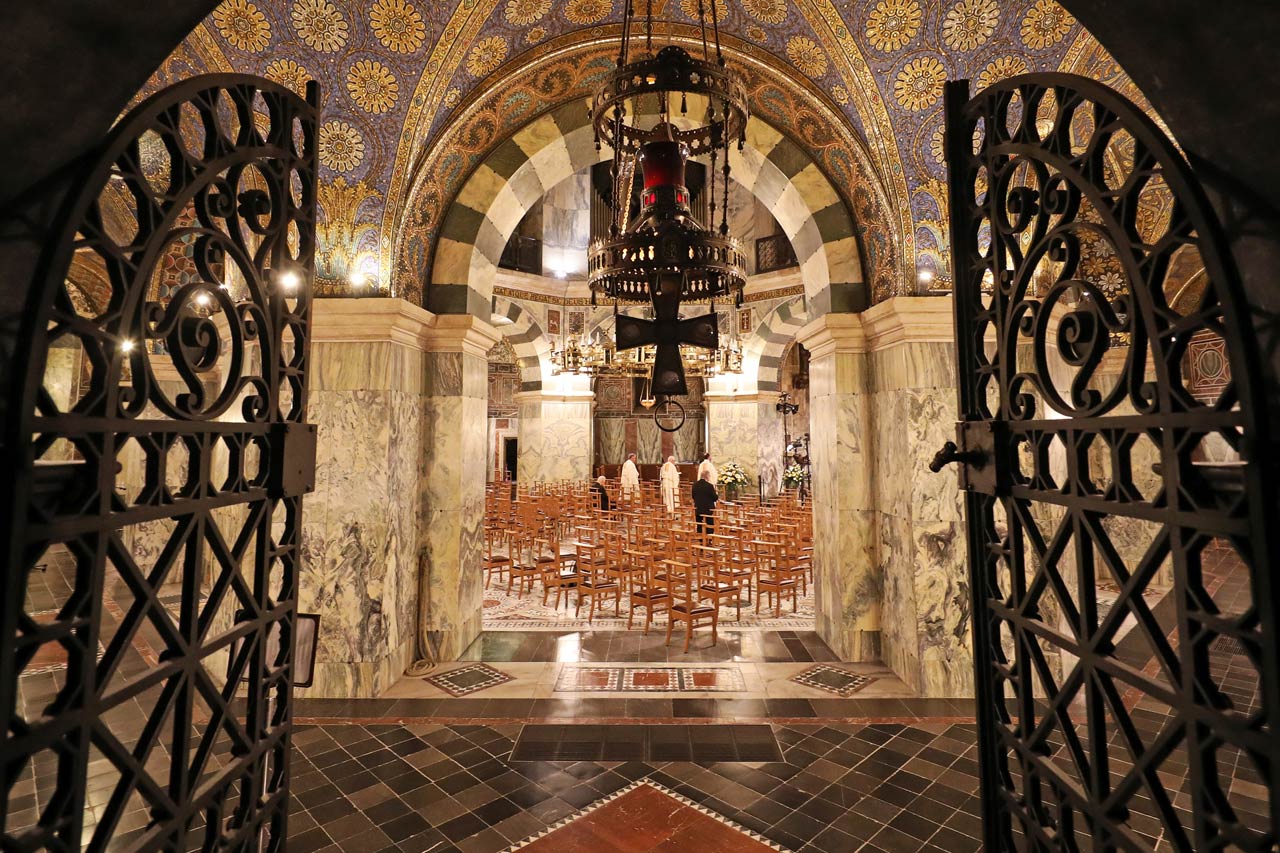

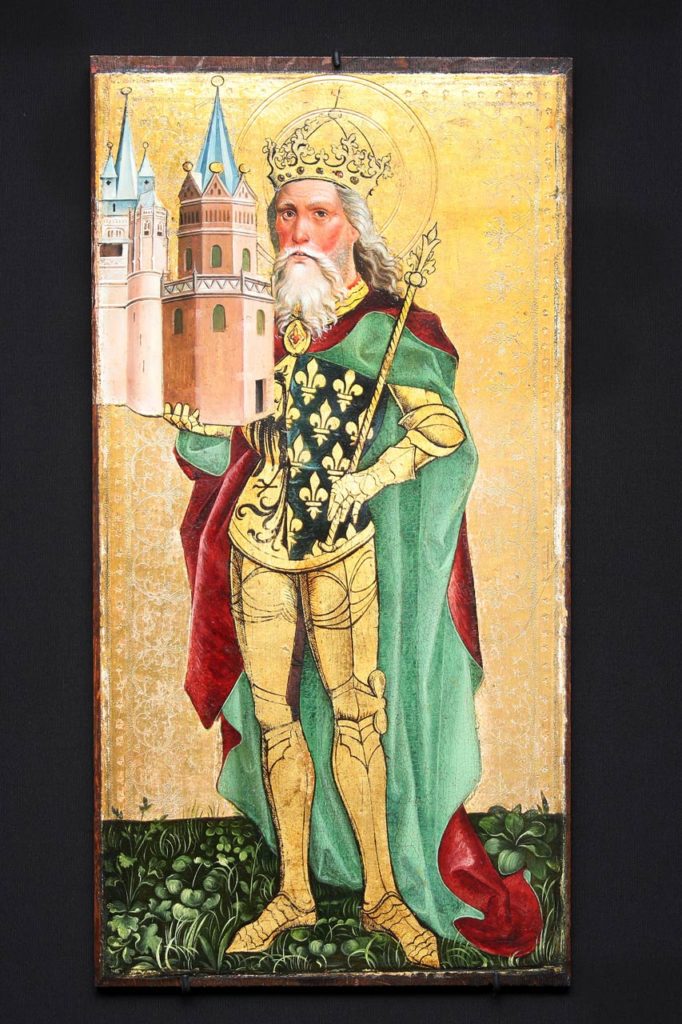

No monumental buildings had been built in stone since Roman times. The Emperor’s Palatine chapel, dedicated to St Mary, was built between 793 and 813 and was pioneering for architectural development in northern Europe. Charlemagne intended for St Mary’s Church to become a complete image of the Heavenly Jerusalem, symbolising the meeting point between the Earthly and the Heavenly. Charlemagne also founded a chapter of canons, in other words a community of clerics who gathered at set times every day to celebrate a service consisting of a mass and breviary. Many depictions that have survived to the present day incorporate the theme of “Charlemagne as the builder of the Church”.

Best of Charlemagne

Charlemagne’s burial

Charlemagne died in Aachen on 28 January 814. That same evening, he was buried in St Mary’s Church, presumably in the ancient Roman Proserpina sarcophagus, which is now on display in the Cathedral Treasury. The very fact that Charlemagne was buried in Aachen Cathedral establishes an indissoluble link between him and the Church.

The myth of Charlemagne:

what remains?

Father of Europe, pious emperor, warlord – opinions about Charlemagne are controversial in today’s historiography. His figure is constantly appropriated for different purposes.

However, there is no doubt that many influences and traditions can be traced back to him.

Aachen Pilgrimage

The Aachen Pilgrimage goes back to Charlemagne’s collection of precious relics. According to legend, he received a set of relics from Jerusalem, which included the robe of the Virgin Mary, the swaddling clothes of the Infant Jesus, the cloth in which the head of John the Baptist was wrapped after his beheading, and the loincloth worn by Christ on the cross. These have been kept in the Shrine of the Virgin Mary since 1239. Since 1349, the relics have been displayed to pilgrims every seven years.

Charlemagne’s shrine and reliquaries

In 1165, Frederick I Barbarossa arranged for Charlemagne to be canonised by an antipope. However, the canonisation was not officially recognised by Rome. To commemorate the anniversary of Charlemagne’s death on 28 January, a solemn high mass is celebrated in Aachen Cathedral on the last Sunday in January (Charlemagne’s feast day).

For the coronation of Barbarossa’s grandson Frederick II in 1215, Charlemagne’s relics were transferred to the Shrine of Charlemagne.

In addition to the Shrine of Charlemagne, numerous reliquaries were created, such as the Bust of Charlemagne and the Charlemagne Reliquary, in which parts of Charlemagne’s bones were kept. The Arm Reliquary was donated by the French King Louis XI in 1481 and bears witness to his special veneration of Charlemagne.

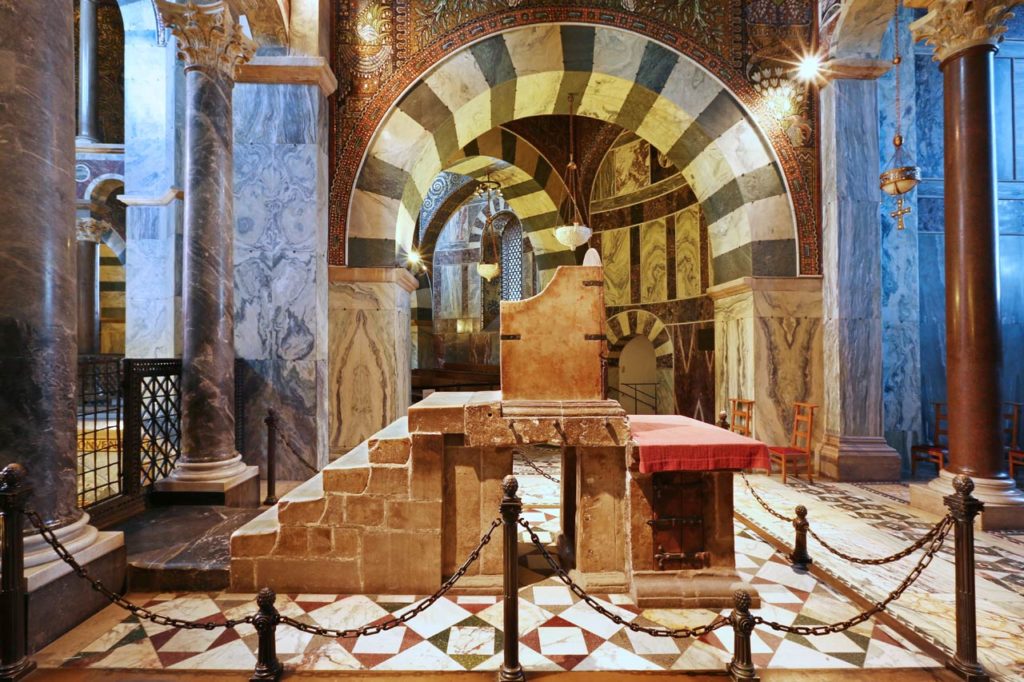

Königskrönungen

With the coronation of King Otto I in Aachen in 936, the function of St Mary’s Church as the coronation site of the German kings was established. Until 1531, 30 kings and 12 queens were crowned in Aachen’s collegiate church. The ceremony on the marble throne in the Hochmünster was considered to symbolise “taking possession” of the empire.

Charlemagne Prize of Aachen

Charlemagne became the eponym for the Charlemagne Prize, first awarded in 1950, with which Aachen harks back to its early European significance. In its founding proclamation, the Charlemagne Prize Foundation invokes the idea of the Christian West: on the one hand, looking back to the Carolingian Empire as a symbol for the unity of basic values and rules, on the other hand, as a guiding idea for the future political and economic unification of Europe.